- Home

- Lewis, David;

River Ouse Bargeman

River Ouse Bargeman Read online

RIVER OUSE BARGEMAN

RIVER OUSE BARGEMAN

A LIFE ON THE YORKSHIRE OUSE

by

DAVID LEWIS

WHY IS A SHIP LIKE A WOMAN?

This book describes the life and times of a Selby bargeman, Laurie Dews. As with all bargemen, he had to know about the important details in life. Two of the most significant of these are your partner and your workplace. This little passage shows the inextricable links between the two.

A ship is like a woman because...

• In port there is always a bustle around her, and a gang of men too

• She has a waist and stays and it takes a lot of paint to keep her good looking

• It’s not the initial expense but the cost of upkeep that breaks you

• When she’s all decked out, it takes a good man to handle her

• She shows off her topsides, but hides her bottom

• And when going into port always heads for the buoys.

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword Transport

An imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright © David Lewis 2017

The right of David Lewis to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor by way of trade or otherwise shall it be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978 1 47388 069 6

eISBN 978 1 47388 071 9

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47388 070 2

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, and Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

Pen & Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire S70 2AS England

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

CONTENTS

Introduction

Chapter 1: Selby’s trade on the Yorkshire Ouse

Chapter 2: Soapy Joe comes to Selby

Chapter 3: A bargeman’s life on the Ouse in the 1920s

Chapter 4: How the Dews family came to work on the river

Chapter 5: A childhood in Selby and holidays on the river

Chapter 6: Picking up cargo in Hull Docks

Chapter 7: Wartime experiences

Chapter 8: New partners at home and at work

Chapter 9: The Journey upriver from Hull

Chapter 10: Coming into Selby and the passage of the bridges

Chapter 11: Mooring up and unloading at Barlby

Chapter 12: Getting paid for the job

Chapter 13: Retirement

Appendix 1: The OCO/BOCM barge fleets

Appendix 2: Making your own entertainment

Appendix 3: Glossary of terms

Appendix 4: The LB craft

Bibliography

INTRODUCTION

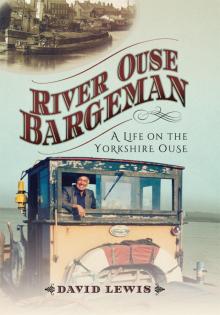

The picture shows a man at ease with the world. It’s a sunny day, he’s in the bridgehouse of his barge, on a river he has worked all his adult life, doing a job his family has followed for over a century.

This gentleman is Laurence ‘Laurie’ Dews, and this book is the story of his family, his working life and of a way of earning a living that had existed for centuries, but at the time the picture was taken in 1986 was waning, and now, by 2016, has vanished forever.

Laurie was part of a team that worked for the seed-crushing mills at Barlby near Selby on the River Ouse. The mills were established by Joseph Watson of Venus Soap fame, just before the First World War. Watson had a fleet of unpowered or ‘dumb’ barges built and hired a group of bargees to work for him carrying cargoes from vessels moored in the docks in Hull. Laurie’s father and grandfather worked on these barges, and Laurie began his work on the river on these craft in the late 1930s. After wartime experience, Laurie returned to the river, and as the 1950s wore on, dumb barges were replaced by powered craft. By 1960, Laurie was experienced enough to become skipper of one of these.

Laurie Dews in the wheelhouse of the Selby Margaret on the River Ouse, 1986. (Laurie Dews)

The trade continued much as before throughout the Sixties, but as time wore on, improvements in transport technology meant that fewer seed-carrying craft docked at Hull, and those craft that did dock along the river had their cargoes carried away in larger lorries on more freight-friendly roads.

At the start of the 1980s, the life-expired powered barges were not replaced, and the corps of bargemen were paid off. Laurie and his mates were found jobs ashore until retirement beckoned in 1987. This last generation of bargemen had a huge store of knowledge and know-how to enable them to pilot their craft along the testing shoals and sandbars of the Ouse, the toughness and dexterity to handle 10-inch diameter hemp ropes, anchors with 100 feet of chain attached and twenty-footlong boat hooks to manoeuvre their craft, and the physical strength to shovel 200 tons of seed into waiting bucket elevators. And when they had done that once, trek back down river to do it all again.

Since 1987, all of Laurie’s fellow skippers have ‘fallen off the hook’ – to use the bargees’ euphemism for dying – and Laurie is the proudly proclaimed ‘Last of the River Bargemen’ to tell the bargemen’s stories and to pass on that knowledge. This book, therefore, is a combination of both Laurie’s first-hand accounts and some factual exposition and expansion of some of the points he raises. Throughout the book, Laurie’s recollections are in italics, the exposition in plain text.

Where do I, as editor, come into this story? In 2008, I began a contract with Groundwork North Yorkshire, working under guidelines formulated by the Heritage Lottery Fund and local Councils to unearth and popularize what was described as the ‘Hidden Heritage of Selby’. Part of the remit was to record the personal stories of people who had worked in one of Selby’s former industries, not only the barge trade, but also manufacturing, agriculture and transport. I first met Laurie in 2010 and since then have had the great privilege of learning about his life and times, enjoying his wonderfully generous personality, and laughing at his anecdotes and saucy songs.

It is therefore a great pleasure to be able to try to put down Laurie’s wit and wisdom in a form that allows others to have a taste of a lost way of life. I am hugely grateful to Laurie for sharing his wit and wisdom with me and patiently explaining that which I did not grasp at first hearing. I have grown to love his ability to spin a yarn. Those yarns are presented throughout the text of this book in italics.

As with all oral histories, the accuracy of Laurie’s words cannot be vouched for. Hopefully, in my exposition of his descriptions I have covered anything that is unclear. Should I have made an error here, the fault is entirely mine. The book begins with an historical overview of the manner in which Selby’s mercantile trade has depended on the Ouse and the developments that have linked town and river. Laurie’s story then follows chronologically as the text covers his family history and tales of his youth, ending with his thoughts in retirement. Sandwiched between

that beginning and end of a tale, the core of the book is more thematic, dealing with the growth of the factories in Selby that Laurie’s barges serviced, the details of the varying skills required at the Selby and Hull ends of the job and the hazards and challenges of the journey in between. These central chapters call upon Laurie’s memories from all parts of his fifty-year career.

In terms of technical matters, in the main weights and measures have been left in the imperial units in which Laurie knew them. When amounts of cargo are referred to, the term ‘ton’ is used throughout here as the Imperial unit of twenty hundredweight which was the standard when Laurie and his father Sam were trading. The metric unit ‘tonne’ did not apply until after they ceased work. Lengths are again generally given in feet and inches as that was Laurie’s ‘lingua franca’. Conversions into metric, where given, are only approximate.

Similarly, modern monetary values have been approximated to give a feel of the worth of a financial transaction, but it is very difficult to convey this accurately, given the need to factor in variables such as the cost of living and variations in the prices of goods. The assumptions of The National Archive’s comparison scales have been used throughout to produce the ‘modern’ values. A variety of nautical terms that Laurie refers to are defined in the glossary that forms Appendix 3.

A briefer version of Laurie’s story was published by Groundwork North Yorkshire in 2011 as part of the ‘Hidden Heritage’ project, and I must thank them for giving me the opportunity to meet Laurie, and lay the foundations for this project.

I must also thank the following for their assistance in preparation of this volume: the archives of the Selby Times, York Press and Waterways World; members of Selby Civic Society; members and the archive of Ye Olde Fraternitie of Selebians; Hull History Centre; Hull Maritime Museum; Hull Peoples’ Memorial; 'Old Barnsley' at Barnsley Market; Selby and Goole Libraries; Yorkshire Waterways Museum; Susan Butler; Chris Drakes; Michael Pearson; Alice Prince, and members of Laurie’s family. My apologies to anyone I have inadvertently missed from this list.

The images in this book are either Laurie’s, mine or are appropriately acknowledged in the caption to the photograph. My thanks to all those who have allowed their images to be used. Permission to use an image in this book does not imply that it can be used elsewhere. A few images remain unaccredited, despite efforts to find the appropriate owners of the copyright. If there is a problem in this regard, please contact the publisher.

David Lewis,

Selby, May 2016

Chapter 1

SELBY’S TRADE ON THE YORKSHIRE OUSE

‘Selby is situated on the west bank of the Ouse which glides by in a deep, broad and majestic stream.’

(S.R. Clark’s Gazetteer, 1828)

The River Ouse does indeed glide through Selby in a quiet yet stately way, but its passage is now almost completely ignored by those who live in town and style themselves Selebians. There are periodic concerns about flooding and the occasional inconvenience on the rare occasions that the road or rail bridges have to swing open to allow a pleasure boat to pass, but for long periods of time, the river has become an irrelevance.

This worthlessness is a very recent development. From Viking ships coming upriver for the battles of Fulford and Stamford Bridge in 1066 and Abbot Benedict’s vision of three swans that led to the foundation of Selby Abbey in 1069, until the final decade of the twentieth century, trade and employment in Selby were centred on the riverside. This chapter describes the history and development of commerce on the river, problems that are encountered in its navigation, and first-hand accounts of those who depended on it for their livelihood.

The Ouse at Selby is no ordinary river. Such is the vastness of the Humber’s estuary that the Ouse, one of its two tributaries, experiences tides at Selby, despite being more than sixty miles from the sea. In fact, Selby was not the furthest extent of the tide. Trinity House, the authority on all matters maritime, explained in 1698

‘Popleton ffery wch is about 4 miles above ye Citty of York (and) we could not reach yt except upon extraordinary Tides.’

Poppleton is around eighty miles by river from the North Sea. It was only with the construction of Naburn Lock in 1757 that the effects of the tidal flow to York and further up the river were restricted. To gain a full understanding of Selby’s river, one needs to begin with a consideration of her tides, meanders and mood swings. A tidal river has many more intriguing properties than one which merely flows in a constant direction at a steady pace. A tide is a mighty pulse of water caused by the gravitational effects of the Sun and Moon. This pulsation of water that brings high tide to the north-east coast of the UK is generated in the Atlantic. A mass of water travels around the northern coast of Scotland and down the eastern one of England, before meeting a similar pulse which has moved up the English Channel. This conflict produces the tidal surge seen as the flood tide that produces a flow that makes it seem that the river is moving uphill.

The actual time of high water on the north-east coast changes the further south one travels. If high water at Aberdeen is at midnight, high water at Whitby is around three in the morning and at Spurn Head 4am. This tide then sweeps into the Humber estuary and high water at Hull will be at around five, at Trent Falls, the confluence of the Ouse and Trent, at 5.30 and at Selby at a little after seven. Poppleton would have been reached around 10am. These periodic changes have a serious effect on river navigation, in three ways, and sailors would have to be aware of the effects of each of them: the length of time the tides ‘run’; the change in depth of the river; and the velocity of the current.

This tide does not run for an equal amount of time on all parts of the river. In general, the nearer to the coast, the longer the flood tide holds sway. Because there are two tides every 24½ hours, at the coast, each flood tide runs for just over 6 hours. At Hull the incoming tide runs for about 5½ hours, but at Selby, for only 2½. Like high water, low water occurs at different times on the river. Since the flood tide lasts a shorter time the further you are from the sea, then the duration of the ebb, when water is flowing back towards the sea, must increase to keep the tidal cycle of a high tide every 12¼ hours. So, if the flood at Selby lasts for 2½ hours, after a very short period of slack water the gentler ebb must begin, lasting about 10 hours.

As the tide comes in, water is pushed up the river, so increasing the river’s depth. The difference in height between when the river is at its lowest and that when all the flood tide has passed is the river’s ‘range’. This range depends on the effect of the Moon’s gravity on the Earth. Tides are highest at new or full moon, and gradually fall, then rise, in the fortnight between them. In its extreme at Selby the range is 15ft (4.7m). If you are mooring your boat on the river, you need to know how much rope to allow for the tide!

The velocity at which water travels upstream depends on the depth of the channel it meets. As the river becomes shallower, the velocity of the flow increases. On the Ouse at Selby, the flood tide runs at speeds up to 8 knots, which is much faster than most river craft can travel under their own power. The power of the current is not to be treated lightly. The Gentleman’s Magazine of August 1811 reports that:

‘John Bateman of Selby, master of the brig William, was proceeding up the Humber when she was driven by the strength of tide upon Whitton Sand [bank]. The rapidity of the current … forced her broadside [lying across the current] and the captain’s wife, two of his children and a female passenger, were drowned as the water rushed into the cabin with overwhelming fury.’

Twice every day, mariners on the Ouse had to get used to these variations in the direction, depth and speed of flow of the river.

A further effect of the tidal flow is a river wave. Under certain conditions, normally around full or new moon, and around the equinoxes in September and March, the incoming rush meets the natural downward flow of the river with such a force that a wave is produced. This effect has long been experienced, and names for it around York

shire reflect the language of the Viking invaders of a millennium ago with Norse-based names such as eagre, aegre or aegir.

The wave is more commonly known as a river bore, which is also derived from an Old Norse word, bara, meaning a wave. Whilst the Rivers Severn and Trent are famous for their inland waves, that on the Ouse can be equally spectacular. The bore marks the leading edge of the tide, and once passed, the pulse of water surges upriver at high speed, carrying all manner of flotsam, making an impressive sight for onlookers, and one has to be wary of if it on the river.

The phenomenon moved Elizabethan poet Michael Drayton to write:

‘When flood comes to the deep,

The Humber is heard most horribly to roar,

When my aegir comes I make either shore,

Tremble with the sound that I afar do send.’

Francis Drake, historian of York, described the bore in 1736 as ‘a strange, back current of water … [it] makes a mighty noise at its approach’. More than a century later, Bulmer’s Gazetteer of the Rivers of the East Riding in 1892 provides more detail:

‘When the tide begins to flow in the [Humber] estuary the waters of the Ouse rise with startling suddenness, and occasionally with considerable violence. This peculiar rising or water-rush is locally known as the “Ager”, a name of doubtful origin, but supposed by many writers to have been derived from Oegir, the terrible water-god of our Teutonic ancestors.’

This wave can dislodge vessels at their moorings. A sudden snapping and loosing of the craft into the river results if the bore and its flood tide are not heeded. River workers were aware of its threat and working keel men in Selby would cry ‘Wild [or “wor”] aegir’ on sighting the crest of the wave.

River Ouse Bargeman

River Ouse Bargeman